The Lingering Impact: China’s Demographic Dilemma

"When Beijing said it would abolish its 35-year-old one-child policy in 2015, officials expected a baby boom. Instead, they got a baby bust." - Liyan Qi, The Wall Street Journal.

2/17/20243 min read

"When Beijing said it would abolish its 35-year-old one-child policy in 2015, officials expected a baby boom. Instead, they got a baby bust." - Liyan Qi, The Wall Street Journal.

"All of China's population policies for decades have been based on erroneous projections," Yi said. "China's demographic crisis is beyond the imagination of Chinese officials and the international community."

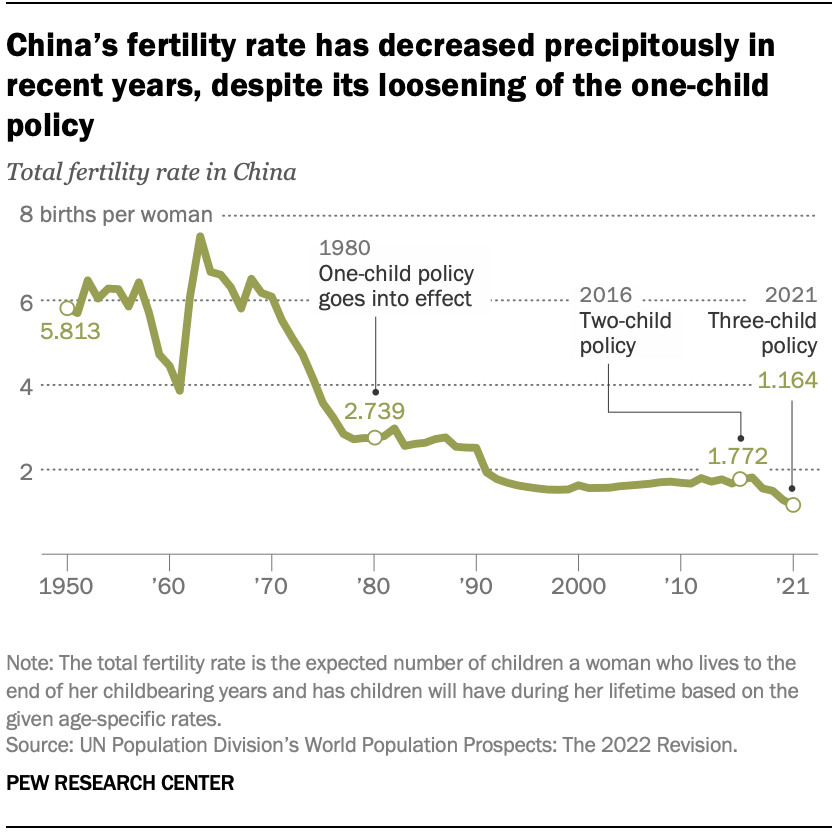

Sometimes, the decisions that we make come back to haunt us. Often much later than when we took them and often in unexpected ways. China's decision of a one-child policy in 1980 is now haunting China as the country is grappling with a declining young population accompanied by abysmal birth rates. Between 1950 and 1970, the Chinese population had increased from 540 million to more than 800 million. In reaction, the government implemented the predominantly voluntary later-longer-fewer policy during the 1970s. This policy aimed to promote delayed childbearing, increase intervals between childbirths, and reduce the number of children.

As a result of this policy, the total fertility rate experienced a significant decline. In 1970, the estimated number of births per woman stood at 5.9, but by 1979, it had dropped to 2.9 births per woman. Despite this downward trend in fertility, concerns about overpopulation remained, leading to the subsequent introduction of the one-child policy in 1980.

Forty years later, here we are. The idea worked a little too well, and now the country is ageing, threatening economic growth. In 2015, the government increased the limit to two children, and in May 2021, it further expanded the limit to three. Then, in July 2021, all restrictions were lifted, coinciding with the introduction of financial incentives to encourage individuals to have more children. The Chinese Communist Party attributes the program to the nation's economic progress and asserts that it averted 400 million births. However, some scholars contest this estimate. Additionally, there are queries about whether the decline in birth rates was primarily influenced by factors unrelated to the policy. The policy has faced substantial criticism in Western contexts due to perceived human rights violations and other adverse consequences.

Today, China's fertility rate is approaching one birth for every woman, which is less than half of the 2.1 replacement rate required to maintain a stable population. Contrastingly, back in the late 1970s, the fertility rate stood at around 3 births per woman.

China witnessed 500,000 fewer births in 2023 as compared to 2022. Young people are citing high childcare and education costs, low income, a weak social safety net and gender inequalities as discouraging factors. In China, 6.8 million couples registered marriages in 2022, compared with 13 million in 2013. For many women, the traditional formula of marriage and motherhood appears less appealing, akin to a raw deal. There are fewer women of childbearing age every year, and in a generation where many grew up without siblings, young women are showing a growing reluctance to embrace motherhood. The traditional expectation of having children is being met with hesitation and reconsideration.

The country is scrambling to bring policies and incentives to promote birth. To encourage more births, local governments have since 2021 rolled out incentives, including tax deductions, more extended maternity leave and housing subsidies. Further plans include a range of subsidies for families raising their first child, rather than just the second and third, to expand free public education and improve access to fertility treatments. The number of proposals in the pipeline shows that the country is taking its ageing seriously. However, it would be decades before we see the change the proposals could bring. All said and done, there is shallow respite in the short term.

Sources:

Family Dynamics and Functioning of Adolescents from Two-Child and One-Child Families in China PMC (nih.gov)

The effects of China's universal two-child policy - PMC (nih.gov)

How China Miscalculated Its Way to a Baby Bust | Mint (livemint.com)

One-child policy - Population Control, Gender Imbalance, Social Impact | Britannica

China's big push for a baby boom | On Point (wbur.org)

China Is Pressing Women to Have More Babies. Many Are Saying No. | Mint (livemint.com)

'Marry & have children': How China plans to improve falling birth rate - BusinessToday

https://www.reuters.com/world/china/time-money-love-china-brainstorms-ways-boost-birth-rate-2023-03-15/

https://www.reuters.com/world/china/how-china-is-seeking-boost-its-falling-birth-rate-2023-01-17/

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/12/05/key-facts-about-chinas-declining-population/ft_2022-12-5_china-population_02/